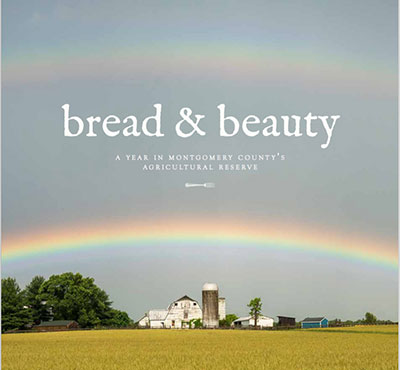

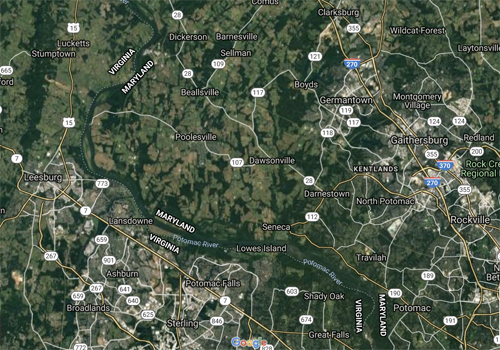

Maryland’s Montgomery County Agricultural Reserve comprises 93,000 contiguous acres in the Washington, D.C. metro region set aside for farming and wildlife habitat. Since it was established in the 1980s, the reserve has created jobs, protected clean air and water, and provided food, respite, and recreation.

But the reserve also exists as layers of human decision-making, beginning with Native American trails and up to the latest proposed zoning amendment. Those layers represent a diverse community—new farmers and farmers whose families have worked the land for generations, those who grow commodity crops and those who grow table crops. People who are passionate about history and devote themselves to restoration and rehabilitation. Others who seek a more soulful rehabilitation in retreat and commune with nature. The diversity is present in the noise and commotion of a hayride and the shush of wind through the trees; in the pencil-line glide of a heron and the mad pedaling of flocks of cyclists.

Like a rich soil, thriving with microorganisms that together make sustaining earth, each person and participant in the Reserve make it a more intricate place by the force of their actions, weaving an invisible network of connections. The seemingly dry planning decisions made under fluorescent lights have created a place of distinction and meaning.

(photo by George Kousoulas)

Until the 1940s, Maryland farmers fed their communities, but post-war changes expanded our pantries, bringing food grown across the country and the world to supermarkets. As local land became less competitive for farming, it became more attractive for suburban development.

About half of the county’s farmland had been converted to non-farm ownership by the 1960s and in the 1980s the county lost an average of 2,346 acres of farmland per year.

It is easy to overlook farmland. Drivers on an adjacent highway sweep by on their way to somewhere else; nearby residents may assume that sooner or later the fields will sprout townhouses. Bread & Beauty, A Year in Montgomery County’s Agricultural Reserve (Claudia Kousoulas and Ellen Letourneau, Bread & Beauty, 2018) is an effort to reveal the decisions behind farming and land use. But because zucchini is more interesting than zoning, Bread & Beauty engages with food, at the table, where we can slow down and appreciate the work of the farmer and the cook.

That loss was slowed when citizens, farmers, politicians, and planners came together to create the Agricultural Reserve, recognizing the value of land set aside for ecological, agricultural, historic, and community purposes. The 1980 Functional Master Plan for the Preservation of Agricultural and Rural Open Space in Montgomery County was the result of a methodical process of analysis, planning, and politicking. It was crafted on previous land use policy that recognized, in the words of Planning Board Chairman Royce Hanson, “[t]here is adequate room for both development and agriculture in Montgomery County.”

The county had already managed its growth based on a concept called “wedges and corridors,” which directed development and focused infrastructure investment along corridors, leaving wedges of low-density and rural development. In the 1970s, a rural development zone limited building to one house per five acres.

(photo by George Kousoulas)

“As I learned about open space conservation and preservation I kept hearing from the old-timers something that I don’t think is always recognized—the importance of the area’s integrity. This is an area whose integrity counts. There is surprisingly little in the way of inharmonious use within it. And what goes along with that is how vulnerable the area is. It doesn’t take much to intrude upon it and when that intrusion occurs, then the fabric is torn.”

-— Law Watkins, local farmer

Changing the expectations of development potential and value could not be undertaken lightly, and the 1980 plan began with a clear statement: “It is in the public interest to preserve farmland.” The plan marshaled its arguments that the goal was not just to preserve individual farms or a way of life, but to:

• Control public costs

• Prevent sprawl

• Preserve regional food supplies

• Conserve energy

• Protect the environment

• Maintain open space

(photo by George Kousoulas)

The Functional Master Plan defended the viability of farming in the region, defined the overall area of the Agricultural Reserve based on soil types and the extent of sewer and water service, and made recommendations tailored to communities and areas within the reserve with tools that included a rural cluster zone and using the state’s Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation Program to buy development rights from farmers.

The plan’s key recommendation was a downzoning, from one house per five acres to one house per 25 acres. But by establishing a rural density transfer zone and corresponding receiving zones, that loss in value was recaptured in a market-based system of transferable development rights that allowed farmers to resell value to down-county developers, who could then increase their projects’ densities.

(photo of Linden Farm Gothic dairy barn by George Kousoulas)

Creating a system to capture value and linking the plan to the county’s established growth management program anchored it in policy positions and the market. As described in the chairman’s foreword, “[i]t is a positive program designed to channel growth into designated growth areas so that market forces are not stopped, but deflected. Preservation and urban policy must complement each other.”

The reserve and its planning implementation tools have won planning awards and become a national model. The authors of the The TDR Handbook: Designing and Implementing Transfer of Development Rights Programs, call it “the most famous, most studied, and most emulated” program of its kind in the United States.

(photo of the Common Ground Market by George Kousoulas)

The reserve’s focus as an active place for farming is constantly being refined. The Montgomery County Office of Agriculture works with the county’s permitting services division to ensure that permitting for farm buildings and businesses makes sense and responds to real issues with an eye to cost and flexibility. Thoroughly vetted zoning amendments adjust allowed uses and intensity in an effort to balance farming with agritourism. And groups such as Montgomery Countryside Alliance and the Agricultural Preservation Advisory Board actively work to fend off development pressures and advocate for farming.

Today, because of this collaboration, the reserve is a place of diverse people and products. It is, both literally and figuratively, open space—a place that allows people to sketch in their own visions and priorities for a rural community.

Thanksgiving Stirrup Cup: Not a scene out of a movie, but an annual event for the Montgomery Hunt, whose riders share an interest in keeping land open. (photo by George Kousoulas)

Driving up Route I-270, you glimpse fields where the reserve meets the road, but get off the highway, slow down, and you’ll see its full history and beauty. Stand with neighbors cheering as the Thanksgiving Stirrup Cup starts its chase, take the winding drive to Button Farm to hear vivid stories of the Underground Railroad, sit on the hard benches of the Seneca Schoolhouse and imagine a lesson taught around the pot-bellied stove, lift your toddler toward a blue sky to pick a crisp apple at Butler’s Orchard.

Montevideo, a Parke-Custis house, connects the county to the nation’s founders while at Sugarland, Gwen-Hebron Reese honors the work of her great-grandfather, Patrick Hebron, Jr., who founded a community on land where he had been enslaved.

After the soil was depleted by early tobacco farms, the Quaker community of Sandy Spring used soil improvement methods like guano fertilizer and crop rotation to return the soil’s fertility. Today, at Rocklands Farm, Greg Glenn moves his animals from field to field, allowing them to feed and fertilize.

At Shepherd’s Hey Farm, Lee Langstaff tends her sheep, which she calls “survival kits”—animals that have been useful for ages to provide nourishment, warmth, skin care, lighting, and parchment. At the Owl Moon Raptor Center, Suzanne Shoemaker rescues injured and orphaned birds, returning them to the wild using her expertise in animal behavior and ecology.

Adults with developmental disabilities are the expert farmers at Red Wiggler, feeding their community and teaching students who volunteer there. People from around the region find calm in the reserve at the Dayspring Retreat Center, where growing food sustains body and soul.

David Scott, Jr. continues his family’s farm, the most recent generation to grow beef, wheat, and corn as market demand shifts. At Plow and Stars, Amanda Cather and Mark Walter grow table crops—a nearly complete menu of vegetables and meat. Mark also brings his students to the farm where he teaches STEM lessons based on real farm life. At the end of the session, his students say they don’t want to return to “civilian life.”

At Calleva Outdoors campers kayak and hike, but also learn about sustainability and green building. Parents are stunned when their children come home raving about growing (and eating) beets.

(photo by George Kousoulas)

The reserve is physical open space, but it is also metaphorical open space. A place where people can determine their work in connection with the land. Those choices range with interests and capacity, but together create a sustainable community. Like building fertile soil, that sustainability is more than a single action at a single point in time. It requires an ecosystem of interests working together. It reaches beyond the natural environment to encompass the economy as well as social relationships and opportunities. And it is an ongoing effort of participation—in the field, in the meeting room, and at the market.

This was originally published here.