Cities offer breakthrough potential for immediate and effective action on the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions and a hotter world, according to a new book, The Urban Fix.

The Urban Fix is the culmination of a long journey for Doug Kelbaugh, an architect and educator in the forefront of environmental and urban design for decades. Kelbaugh designed and built one of the nation’s first passive solar houses in 1973, and he was one of the first advocates of transit-oriented development in 1980s.

Since then, environmentalism and urbanism have been passions of Kelbaugh, and they come together in The Urban Fix—a book that makes an important contribution to humanity’s search for solutions to climate change, one of the most pressing issues of our time.

But Kelbaugh identifies and explains an area of change science and policy that has been given little attention—the concept of urban heat islands (UHIs). Urban heat islands cause cities to heat up far more than surrounding suburbs and countryside.

UHIs would seem to be a major disadvantage of cities in the era of climate change, but Kelbaugh shows how we can turn this disadvantage into opportunity. Worldwide, heat waves kill more people than any other kind of natural disaster, he reports, and these heat waves are likely to become more common and severe.

“Fortuitously, the local ways to mitigate and adapt to UHIs are essentially identical to ways to address global climate change,” he writes. “And because they are a shorter, perhaps a 10-year challenge, rather than a 100-year challenge, UHIs can more immediately and effectively rally individuals and societies to change their behavior.”

To explain why UHIs, and cities, are key to both climate change mitigation and adaptation, Kelbaugh explores seven related concepts, in the order listed below. He calls this “connecting the dots”:

- Climate change is an existential threat to mankind.

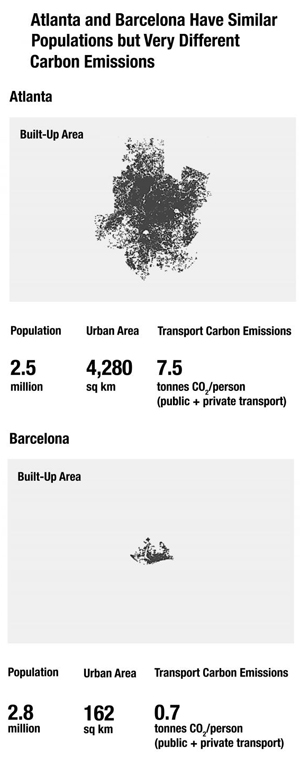

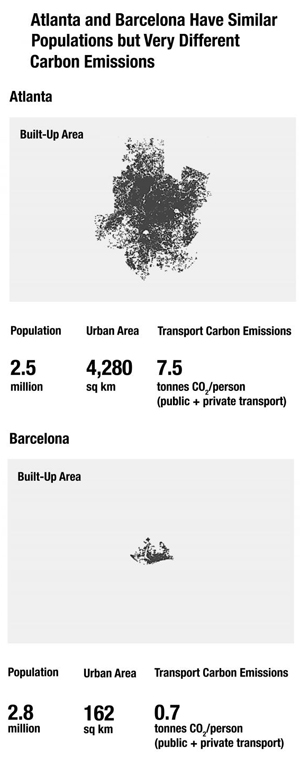

- Paradoxically, the places where mankind has the greatest impact, cities, reduce environmental impact and carbon emissions. People walk and bike more in cities, and urban buildings use less energy than the suburban and rural counterparts.

- Also, paradoxically, the places with the greatest population, cities, are reducing overpopulation. When people move to cities, they have smaller families—especially in developing countries, where rural birth rates are very high.

- Urban heat islands make cities hotter than the rest of the planet, but they also offer an opportunity to address climate change at the local level.

- Addressing UHIs simultaneously helps to mitigate, and adapt to, climate change.

- UHIs are a more immediate threat than long-term climate change, so they prompt people to act. That action can take place locally and benefit local communities immediately.

- Therefore, cities and urbanism are the last, best, hope for humanity in dealing with “the wicked problem” of climate change.

Causes of urban heat islands

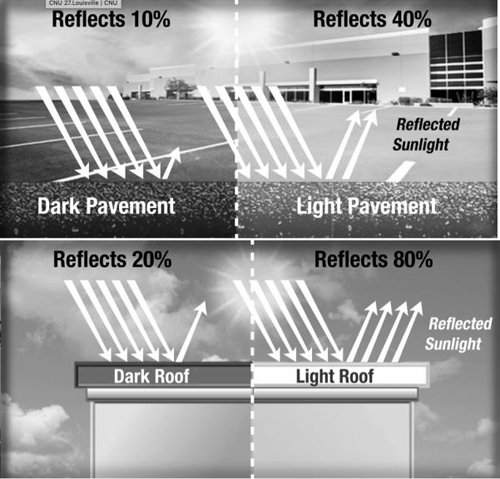

Major causes of UHIs are dark-colored buildings (especially rooftops), dark pavement, greater proportions of buildings and pavement to greenery (which absorbs heat and converts it to photosynthesis), and, finally, waste heat—through combustion, machines, and air conditioners.

He explains a term, “urban albedo,” that has profound implications on urbanism but has been little discussed among urbanists. Urban albedo is the percentage of sunlight that is reflected back away from Earth in cities, reducing both climate change and UHIs.

Urban albedo can be addressed in three ways: white roofs and light pavement; Green roofs and landscaping (especially trees); and solar panels, which convert solar energy to useful power. White roofs and light pavement, and reducing pavement itself, may have the greatest potential. White and light-colored surfaces—primarily roofs and pavement with a high solar reflectivity index (SRI), reflect most of the solar radiation back into space “before it gives up any of its heat,” he explains. White roofs can increase SRI from 20 percent to 80 percent, and are three times more effective than green roofs at combating climate change, Kelbaugh reports.

White roofs not only reduce UHIs, but also cool the buildings themselves. This has profound implications, because it reduces the need for air conditioning. Before reading The Urban Fix, I had no idea of how large air conditioning looms as a climate issue. “Improving AC is arguably the single more effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” Kelbaugh writes. Simply replacing refrigerants that damage the atmosphere would reduce emissions considerably more than half of the world’s population giving up meat, or replanting two-thirds of degraded tropical rain forests. “Making the (air conditioning) units more efficient could double that” impact, he says. Reducing the need for AC, and making it more efficient, also means less waste heat spewing from these machines.

Roofs and pavement need constant maintenance, and this reality offers an opportunity to drastically reduce the energy absorbed by buildings and infrastructure.

Under the asphalt of the streets of my city, Ithaca, are yellow bricks (yes, I live on a yellow brick road). I wonder: Could uncovering these bricks be a climate and UHI solution? They can be maintained fairly easily. They last a long time. They slow down traffic. Even if that is not possible, light-colored pavement makes a big difference. While dark asphalt has an SRI of 5 percent, white concrete reflects 80 percent of sunlight. Los Angeles has begun addressing the problem of dark pavement and lack of landscaping, and the city believes that it can cut temperatures by three degrees in the next 20 years. One test application showed a local, 10-degree reduction in heat gain. Weeks later, residents told the LA Daily News that they could already feel the difference.

Reducing parking can help with both climate change and UHIs. That’s another reason to get rid of minimum parking requirements, besides the fact that they damage cities and make little economic sense. “Parking is the single biggest land use in most cities; there’s more land devoted to parking than there is to housing or industry or commerce or office,” notes parking guru Donald Shoup, quoted in the book. Less parking means more vibrant cities, less driving, and less waste heat.

The wonder of trees

Planting trees in cities may have the most immediate impact on heat islands and climate change. “Planting these multitaskers in cities is a win in so many ways to mitigate and adapt to both climate change and UHIs … It is an appealing, low tech, time-tested practice that sequesters CO2 and reduces air pollution, soil erosion, and storm water runoff, not to mention providing oxygen, habitat for small animals, shade in the summer, and more.”

Trees have been “credited with increasing real estate values,” especially along tree-lined streets. By planting trees, wouldn’t cities be able to boost tax revenues while both adapting to and mitigating climate change?

Cities themselves mitigate climate change, since urban residents drive less and live in buildings that tend to use less energy per household. The movement toward urban living is a worldwide demographic trend; therefore, encouraging people to live in walkable neighborhoods is politically and technically feasible.

This book is filled with statistics and numbers, and that makes for difficult reading at times. If I have one criticism, it is how Kelbaugh deals with the level of climate change threat. The tone of The Urban Fix is all over the map on this topic, from arguing that climate change action is justified on insurance grounds, to, in essence, proclaiming a planetary five-alarm fire now. One example of this inconsistency is when he mentions that “recent predictions are for roughly 3 feet of sea level rise this century,” even if we don’t control emissions to meet current targets. He follows that statistic with this quote: “Many experts believe that even if emissions stopped tomorrow, 15 or 20 feet of sea level rise is already inevitable, … .”

Maybe that’s a reflection of the uncertainty of future scenarios, but the beauty of the action Kelbaugh is proposing is that it doesn’t require a 20-foot sea-level rise as justification. Climate mitigation and adaptation in cities makes sense, even if Southern Europe doesn’t become a desert and many cities are not inundated.

Another advantage to addressing UHIs is that action can be scaled up and down the levels of government and geography. Implementation could be led by local communities and nonprofits, and funded by state and local governments. Responses could be supported nationally and internationally. The actions that Kelbaugh recommends have been all-but-ignored in climate discussions—but they should be at the top of the list.

I hope that the ideas in The Urban Fix gain wide currency. The book dramatically expanded my understanding of how climate change can be addressed by urbanism. That’s a first step, and it’s one that any urbanist can take by reading The Urban Fix.

This column was originally published here.

Public Square: A CNU Journal (Congress for the New Urbanism)

Congress for the New Urbanism on the web

Congress for the New Urbanismon Facebook